Working out of a London studio in 1884, Sutherland Macdonald was one of the first professional tattoo artists working in England. In 1902, he was interviewed for a Pearson’s magazine article, titled “A Tattoo Artist.” Looking back on this article reveals both some of the reasons Victorian got tattoos and a few of the perceptions of the art at the time.

Macdonald primarily tattooed men, but not exclusively. In fact, he was known for being able to realistically tattoo blush on the face, and women went to him specifically for this early form of cosmetic tattooing. Military men and royalty both came to him for insignia and crests, serving as both status symbols and, for soldiers, as identifying marks in case of death. Macdonald tells the story of a client who survived the sinking of the SS Drummond Castle in 1896 and during this near-death experience had decided to have “some distinguishing tattoo mark placed upon him, so that in future he could be identified easily in case of an accident.” This man ultimately had his name and address tattooed by Macdonald. Tattooing as a means of identification was in the public eye at the time, as the Tichborne case (where a man claimed to be the missing heir of the Tichborne Baronetcy) had just been settled on the basis of the true heir being known to have distinguishing tattoos.

Tattoos often had sentimental purposes as well. Researchers with the Digital Panopticon, a database of convict descriptions–including tattoos–from 1793 to 1925 in Britain and Australia, found that names and initials of loved ones and family were by far the most common tattoo. While it’s likely that Macdonald tattooed many initials, clients came to him in order to memorialize other things as well. One military officer with seven scars had each “tattooed with inscriptions giving the date and the place where each wound was received.”

Tattooed Victorians weren’t without a sense of humor, either. Macdonald describes another officer, who had socks tattooed onto both feet and after being bitten by a dog on one foot, returned to have the tattoo touched up in the style of darning stitches. This same man had almost his entire body tattooed, with the exception of his head, neck, and hands, and passed away before the article was written. Even during Macdonald’s lifetime, his art wasn’t preservable beyond the occasional picture because of its temporary canvas.

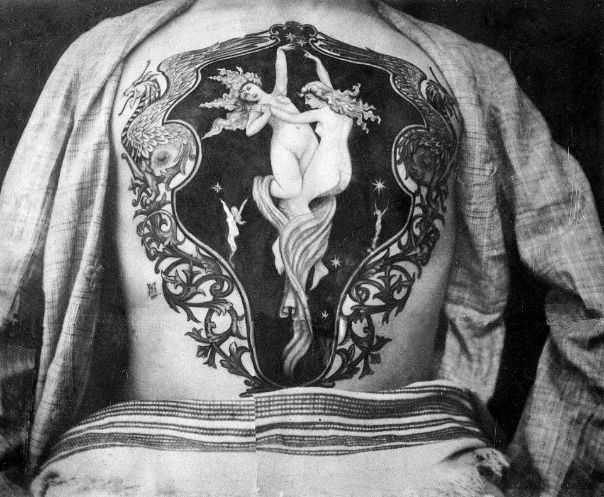

The author, Gambier Bolton, touches on this aspect of temporality as he “regret[s] that the results of [Macdonald’s] patience, and his wealth of minute detail, should all eventually be lost to the world.” Bolton stresses that Macdonald’s tattoos are “Art with a capital A,” arguing that they should be considered alongside the art displayed in museums. Macdonald himself stresses the distinction between “tattooIST” and “tattooER,” considering himself among the “professions” rather than the laborers like “bricklayers” and “plumbers.” Tattooing, when considered through this framework, becomes understood as a type of “civilized” high art and separated from preexisting indigenous tattoo practices. Bolton ends the article by saying that:

“[Tattooing] is dying out among most of the uncivilized races, as the missionaries of all creeds fight hard against the practice wherever it is met with. They appear to think that tattooing is in some way mixed up with heathenish rites and other forms of superstition. Amongst the civilized races, however, its popularity appears to be on the increase, and so long as an artist like Sutherland Macdonald can be found it will continue to flourish.”

Bolton gets at a tension in Victorian tattooing, which is that as indigenous cultural practices were being wiped out through colonization and understood as signs of uncivilized societies, tattooing became increasingly popular in England. This tension can also be seen in the captivity narratives Victorian tattooed ladies used to explain their appearance. In both cases, there is an attempt to create a separation between “civilized” and “uncivilized” types of tattooing.

This is so cool! It is really interesting to learn about the history of tattoos, and how they were perceived by society.

By: evaallii on November 20, 2023

at 7:32 pm

The Victorians had some pretty cool tattoos, and I think it’s interesting how we can see the cycle of permanent make-up repeating itself— though today it’s probably more focused on lip blushing and micro blading rather than blush!

By: mwbarron on November 30, 2023

at 9:10 am

So interesting! I think, as with many things, we often assume because the Victorians were doing it so very long ago the art must have been much less intricate or taken more seriously with their limited technology and the newness of the practice to the Victorians. However, this post elucidates the great skill the artists of the time had, as well as the fun people have always had with the technology (I love the darning touch up).

By: catdippell on December 16, 2023

at 4:16 pm

Kaia, I learned so much from this fascinating post. I didn’t know a lot about Victorian tattooing practices, but I’m so interested in what an evolved art form it was during this period. Your analysis of the colonial politics is particularly insightful — that tension between the popularity of body art among Victorians and the eradication of colonial peoples for whom tattoos were an important cultural practice.

Also, I have to say that Macdonald’s tattoos are just gorgeous!

By: amartinmhc on December 23, 2023

at 3:17 pm