In the 19th century, heavily tattooed men could be found performing in dime museums and circus freak shows. This shifted, however, in the 1880s as tattooed ladies began to replace them. In order to explain their appearance, both tattooed men and ladies promoted themselves with false narratives of captivity and forced tattooing by indigenous people. Tattooed men were more likely to use narratives of being stranded on islands and tattooed by the islanders, since many came from sailor backgrounds. As more women took to the profession, they adapted commonly used captivity narratives in their self-promotion to thrill and entice audiences.

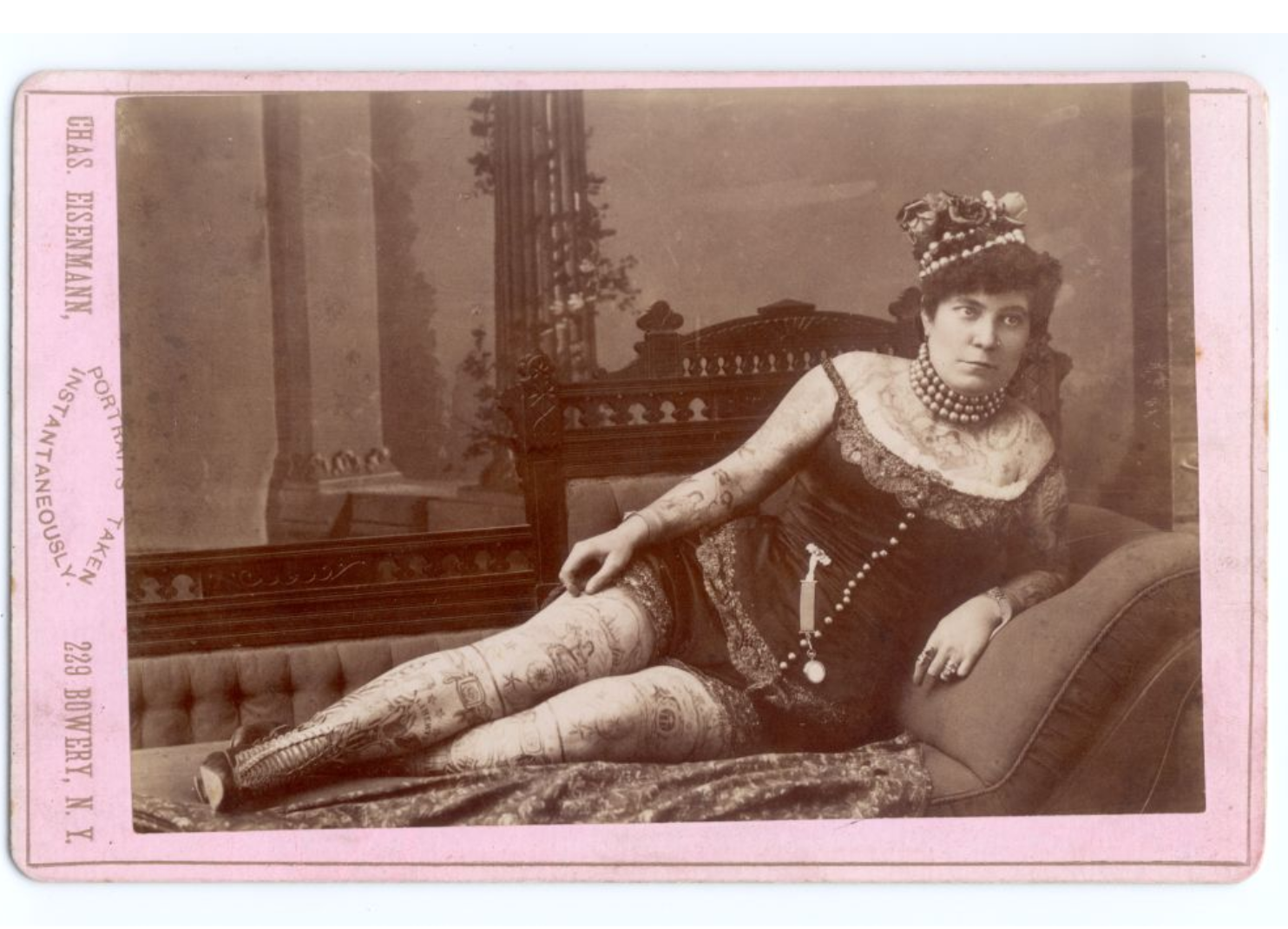

One such woman was Nora Hildebrandt, who, along with Irene Woodward, was one of the first tattooed ladies, debuting at Bunnell’s Museum in New York in 1882. Nora’s advertised backstory was that while traveling in the Wild West with her father, she was captured by the Lakota and Sitting Bull himself. Sitting Bull ordered her father, who had learned to tattoo as a sailor, to tattoo her whole body under threat of death. This he did for six hours a day for a full year, until he purposefully broke his needles. Her father was killed for this, but she lived on to be rescued by General George Crook. Blinded by the pain, she was found in a Denver hospital by a circus owner and sideshow manager, who paid to send her to New York, where she recovered her sight and began performing.

In reality, Nora never lived in the West and her “father” was in fact her common-law husband Martin Hildebrandt, who was a well established New York tattoo artist at the time. Martin was the one to tattoo Nora but, besides that, all the facts of Nora’s origin story are false. Creating this false narrative shifted the responsibility for getting tattooed away from Nora, allowing her womanly purity and scandalous appeal to coexist. Like many sideshow acts, part of the draw for Nora’s audiences was that she occupied an intersection between what the Victorians saw as an “uncivilized other” and the body of a “civilized lady” close to home. Viewers could engage with their fear of violent Native Americans and satiate their fascination with the other without having to actually venture away from the safety of the circus tent. Nora’s claim that she was captured by Sitting Bull himself has the added effect of capitalizing on his fame at the time, having defeated the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn a few years before in 1876. Her use of a captivity narrative in self-promotion both promises audiences access to recent history and Native American culture without substantially challenging the division between self/other or the associations between tattoos and a lack of civility.

Further Reading on Indigenous Tattoo Practices:

How the Samoan Tattoo Survived Colonialism

Apo Whang-Od and the Indelible Marks of Filipino Identity

‘Before colonization, tattoos were normal.’ Traditional Inuit tattoos were almost wiped out

Work Cited:

Osterud, Amelia Klem. The Tattooed Lady: A History. Second ed., Taylor Trade Publishing, 2014.

This is interesting, I have really never seen photos from this time period of people with tattoos. It is interesting to learn about the relationship between tattoos, history, and spectacles. Great post!

By: evaallii on November 20, 2023

at 7:30 pm

Again, Kaia, I learned so much! I didn’t know about this inextricable relationship between tattooed people and settler colonialism/ anti-indigenous racism, but it is very interesting. You do such a great job of unpacking this nexus between freak show performers and US colonialist history.

By: amartinmhc on December 23, 2023

at 3:24 pm