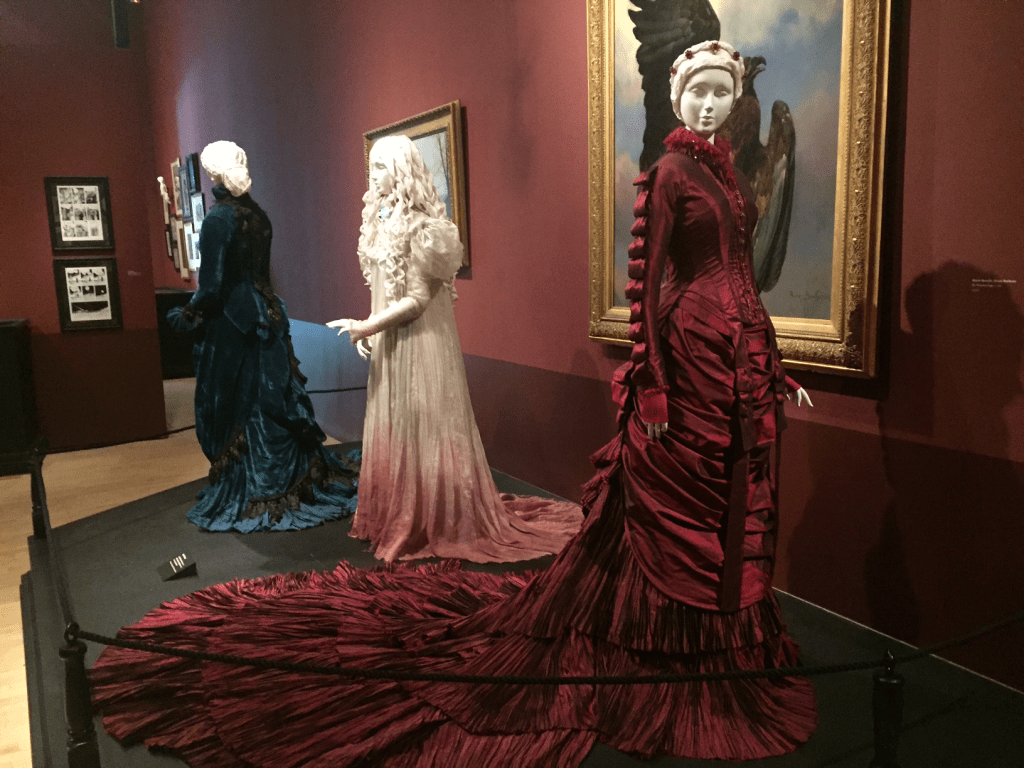

Crimson Peak costumes at the FIDM, designed by Kate Hawley.

One of my favorite films is Guillermo del Toro’s Crimson Peak, a love letter of sorts to the gothic romance genre, and the Victorian gothic in general. The film’s costumes have been exhibited on several different occasions at various places, so I’ll be discussing the costumes broadly, as well as the insights into the process that some of the displays include. I’ve sourced my images from the following exhibits: the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising Museum, 2016, and the Art Gallery of Ontario (& other locations) where a larger Guillermo Del Toro exhibit happened in 2017-18. Also, a fun fact I’ve been sitting on for a while: Del Toro refers to his second home where he keeps his extensive collection of horror paraphernalia as “Bleak House” after the Dickens novel.

Spoilers interspersed below — beware!

Additional costumes shown in the Guillermo Del Toro: At Home With Monsters exhibit at the AGO. Left to right, Lucille Sharpe’s “drop of blood” dress, Edith Cushing’s nightgown, the ghost of Edith’s mother, the same dresses of Lucille and Edith pictured again.

Some brief background on the film: It follows the bright (in both mind and color scheme) Edith Cushing, an American woman and aspiring writer. She is pulled into the dim and dangerous world of the Sharpe siblings, the very last of a crumbling line of minor aristocrats. There are, of course, ghosts, murder, and dark traumatic pasts abound. It is set at the very cusp of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, and straddles the line between the archaic and modern in its characters, narrative, and visual associations. The film plays deliberately with the themes, tropes, and images associated with the era, relying on not just a historical familiarity with the Victorians but a cultural familiarity/knowledge of our modern engagement with the era and its resonances.

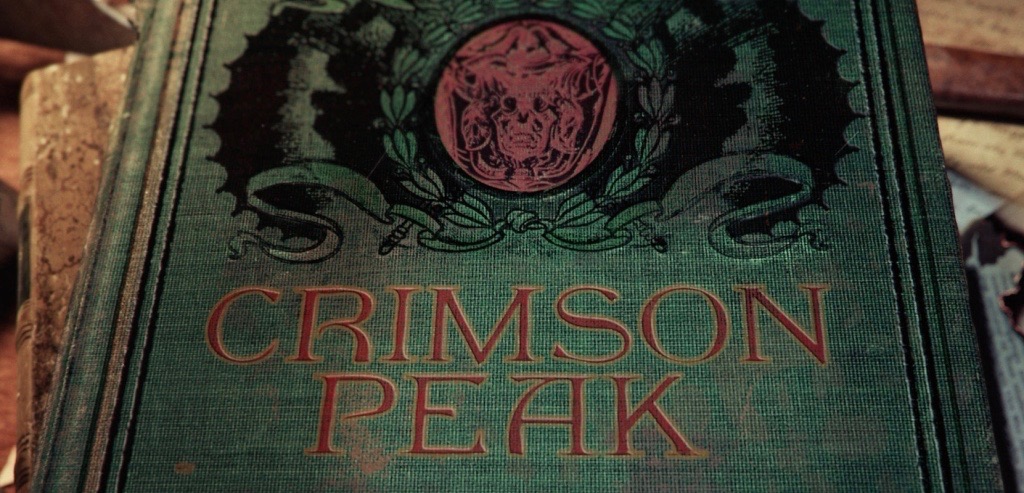

Guillermo Del Toro’s investment in visuality and his use of it to convey meaning is largely what has inspired this post in the first place. Crimson Peak is a feast for the eyes; the costumes were carefully sewn in multiples with handmade appliqués and finishings, the house was a sprawling physical set that engulfed the actors, and so on. There is an immense amount of care to how the characters and world are presented to us visually. Much of the depth in the characters’ histories, for example, is not textual; extensive biographies were created and character work done without any of it being directly present in the dialogue. The visual language of the film, however, richly expresses and cleverly suggests what we are not told. Del Toro and his costume designer Kate Hawley rely upon visuality as a means of conveying all that is not textual, the external appearance of the characters and sets becoming representations of interior worlds. Crimson Peak’s engagement with Victorian media and genre conventions also requires a sort of meta-engagement with the film as well, sometimes making use of visual cues that signify little to most, but hold immense meaning to those who know how and where to look. Viewers are immediately clued in to how they are supposed to engage the film a mere few minutes in. We are situated in the present when a book titled Crimson Peak opens to an illustration of Buffalo, New York, beginning Edith’s story by situating us in a novel we know she will go on to write after the narrative’s conclusion. This places viewers in a specific historical and literary space from the get-go, bringing all the associated tropes and images into the conversation and analysis through this choice.

The presentation of the film’s title. Created digitally, along with the end credits, by Ron Geravais and Dave Greene of design studio IAMSTATIC. More information about their process can be found in Art of the Title’s 2015 interview of the designers, via https://www.artofthetitle.com/title/crimson-peak/.

Many of these images that engage the genre and its baggage are created through the way the characters are attired; Edith is the “new woman,” later a “woman in white,” Lucile the “madwoman in the attic,” etc. The film’s costuming is unquestionably one of the most impressive aspects of its production, both in its narrative purpose and in the skillful craft utilized to make the pieces. Each garment works to establish visual motifs associated with the characters, the silhouettes accordingly loose and flowing or sharp and constricting, the fabrics chose to catch or absorb the light. Lucille, the moth; Edith, the butterfly. Every anachronism in the film is deliberate, and deviates from strict verisimilitude in order to convey meaning. The most discussed anachronisms in the film are the costumes of the Sharpe siblings which look to be of the natural form era, some twenty years before the present day, 1901. They are attired in dark and precisely fitted clothing, enveloped in velvets, always appearing out of place and out of time when they engage with society in the modern Buffalo. Despite there being no historical likelihood of one wearing clothing so long out of date while running in the circles the Sharpes do, it is incredibly accurate to the past decade. Here their visage is used to convey their occupation of the past and entrapment in their family history/home (they wear their parent’s clothing, after all). It makes it perfectly fitting that they are always in darker shades, weighed down, entirely unlike the bright silk and airy cotton voile we see the other cast wear.

The costuming of Lucille Sharpe. The color palette and form of Lucille’s gown visually ties her to the house. The center photo shows progress on passementerie used for Lucile’s costumes, the design recalling the shapes of Allerdale Hall itself.

Lucille exemplifies this in particular; she moves through the Allerdale Hall as though a part of it, which is reflected in her garments. She melds with the walls, made of the same cold and harsh visual language. Seen in Hawley’s sketches, the architectural elements of the house were replicated in the gown’s construction. At the start of the film as well, her “drop of blood” dress is a taste of the distinctly crimson ghosts to come later. As the character most inextricably bound up by her past and childhood traumas, her intensely visual link to the house amplifies the sense of haunting and entrapment. So very defined by the past, she breathes, bleeds, and decays with the house.

The choice to costume Lucille (and Thomas as well, but to a less dramatic extent) in this manner is impactful even for those not knowledgeable of dress history. It creates two visually distinctive sites, conveying the characters’ psychologies and relationships to their respective haunted pasts; one can discern which world the characters come from in but a glance. When those worlds collide, so do the visual motifs in the costuming. With the Sharpes at their most vulnerable — also their most dangerous, in Lucille’s case — the dark layers that envelop and constrict them are removed. For both this removal of layers takes place in scenes with Edith, her presence disrupting the disconcerting equilibrium they’ve created, narratively, interpersonally, and visually. Thomas is his least formally-attired in the film during a moment of intimacy, and Lucille is only once seen dressed down at the climax. There, she and Edith face off as visual equals, both bloodied in their flowing nightgowns with hair trailing behind them.

Edith furtively moves through Allerdale Hall, wearing her “Nancy Drew” dress during her investigative escapades. The otherwise dull light catches on her soft and gold silhouette, shimmering and dissonant with the set.

For the majority of the film though, Edith’s costuming is the antithesis to the static, past-oriented world of the Sharpes. Hawley costumes her in ways that emphasize her contrasting values and mode of living with the rotting Allerdale Hall. Edith’s world is brilliant, progressive, and certainly touched by the macabre but not consumed by it. There is almost always a tinge of something dark that accents her outfits, though it can take a keen eye to find it. For example: amidst the black at the neck of her walking suit a minute skull pin is nestled, the same one used to pin her tie in a later scene. Or take the gleaming golden-yellow of her “Nancy Drew” dress (above, left, and right), which is complimented by a stark black bow dangling from her neck. Yet when she moves into darker environments, she still remains just as out of place as the Sharpes are in Buffalo. The flowing yardage of mid-1890s skirts and the weightless quality of the puffed sleeves makes her stand out as a bright speck embodying the new and modern amidst the decaying gothic world she is transplanted to.

To the left, Edith’s walking suit worn at the beginning of the film. To the right, a walking suit at the Victoria & Albert museum, c. 1895, via https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O13856/walking-costume-doucet-jacques/

There is also the anachronism of our protagonist’s costuming to consider; a notable and rarely discussed aspect of Edith image is that she, too, is not attired appropriately for the year the film is set in, though the discrepancy is less severe than the Sharpes’. Her visual presence is especially powerful in the ways it engages Victorian culture, drawing upon recognizable media of the time to make a statement about her character. To many, the difference of several years is not noteworthy but the choice itself remains significant. Edith evokes a very particular image — that of the “New Woman,” with its ties to the Charles Gibson illustrations that produced the eponymous Gibson Girl type. Putting Edith in this suit and other such garments creates visual associations between her and the image of the emancipated woman, who engages eagerly with the freedoms afforded to her by shifting social dynamics.

Left, a Gibson Illustration for Scribiner’s, published 1895, via https://www.loc.gov/item/2002720198/#. Right, costume designer Kate Hawley’s sketches of Edith Cushing’s costuming.

Most of Edith’s dresses could be more accurately dated to 1895-1899 rather than 1901, when the puff on the sleeve begins to drop and the front of the bodice gains body in the pigeon-breasted silhouette. She is clearly evocative of this late 1890’s modern woman, the type you might see on cycling advertisements that remind one of the era’s feminist discourses. Hawley seems to be directly inspired by these images and the associated type of woman. Edith is seen with a bicycle in one sketch, and in the film she recalls women’s shifting place in the workforce as she types her manuscript in an office, bespectacled, looking to improve her chance of being published by modifying her perception.

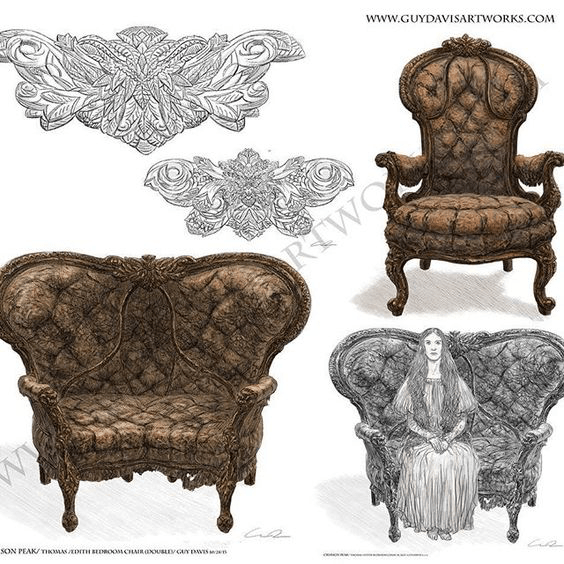

Edith earlier in the film, and later in the same chair. Doubles of such set pieces were made to create this sense of smallness as her circumstances become increasingly dire.

The film also uses visuality in ways that have great effect while using tactics difficult for audiences to identify. The environment itself is subject to subtle changes as the narrative progresses that (similarly to many of the costuming details) are unnoticeable even as they feed influential visual information to you. My favorite example is how as Edith’s situation becomes more desperate and chances of escape look less likely, the furniture she sits in changes size. The weaker she grows, the larger the chair she sits in; her psychological state comes through in this changing physicality that creates an illusion of diminutiveness. These set pieces, among many other props, are featured in the At Home With Monsters exhibit. All these components of Crimson Peak‘s visual environment were crucial to the creation of depth. The film’s visual construction requires an almost literary approach, making close looking rather than close reading the preferred method of analysis. If you’ve seen the film, did you notice that the word “fear” is subtly incorporated into the background sets, even in the wallpaper?

Concept art of the wallpaper in Allerdale Hall by Guy Davis. The word “fear” is worked into the moth-like shapes, almost imperceptibly, via https://www.instagram.com/guydavis.art/.

I believe Crimson Peak can be endlessly examined in its tactful use of visuality blended seamlessly with its storytelling, but at some point this post must come to an end! I’ve seen the film countless times since its release, and continue to identify previously undiscovered uses of visual language signifying things I could not have known I was missing. I’ve often wished I had had a chance to visit these exhibitions myself, as I’m certain an in-person look at the costumes and props would reveal even more detail and care than I’ve discussed here. The meticulousness of Kate Hawley’s work on the film is commendable and always a treat to dig into, as it’s given so much life to Del Toro’s vision; I find that the more closely I look, the more fruitful my readings. The visual subtext in Crimson Peak is abundant, as is its engagement with Victorian visual culture, making it irresistible to explore just how we might look deeper yet.

Thanks for reading!

Works Cited

Crimson Peak. Directed by Guillermo del Toro, Universal Pictures, 2015.

FIDM Museum. “Crimson Peak: Part One.” FIDM Museum, 17 Apr. 2016, fidmmuseum.org/2016/04/crimson-peak-part-one-1.html.

FIDM Museum. “Crimson Peak: Part Two.” FIDM Museum, 20 Apr. 2016, fidmmuseum.org/2016/04/crimson-peak-part-two-1.html.

All other images are from the listed exhibits, the film itself, or Kate Hawley’s personal images and artwork provided for said exhibits. Conceptual artwork is all sourced from Guy Davis, via https://www.instagram.com/guydavis.art/.

[…] spent a while going on about the costuming of Guillermo del Toro’s 2015 film Crimson Peak here, but would like to elaborate further on some of the film’s content that intrigues me, beyond […]

By: Distortions of the Domestic in Crimson Peak | Victorian Visual Culture on December 16, 2023

at 4:01 pm

Incredible post about Crimson Peak, Cat! I was introduced to this film the last time I taught this class when a student wrote a fantastic paper on the film and its costuming. Indeed I agree about the way that Del Toro and Hawley create dense visual languages that are full of implicit and explicit narrative. I so enjoyed reading this, and in particular the way that you brought your expertise on fashion history to bear on this endlessly fascinating film.

By: amartinmhc on December 24, 2023

at 9:43 am