I was first introduced to Yinka Shonibare’s work when I saw his piece Gay Victorians (pictured below) in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art a few years back. The patterns and bright colors of the fabric caught my eye. The fabric he uses in this work, and many of his others, is a cotton with an Indonesian batik design. Often seen in West African fashion, this fabric was first introduced to Africa by a Dutch company through colonization. It can also be found in London markets, which is where Shonibare buys it. Just the fabric itself has a complex history which is deeply entwined with European colonization of Africa and the movement of goods which helped to fund it. The dresses are made in the bustled silhouette of the 1880s. They’re beautiful to see in person, especially the way the patterns and crispness of the cotton interacts with the many layers of the skirts.

Looking further into Shonibare’s work online, another piece caught my eye. Decolonised Structures (Queen Victoria) is from his larger Decolonised Structures series, which was created last year. This time, a batik pattern has been painted onto the surface of a statue of Queen Victoria. By covering the entire surface with the pattern, without delineating skin or clothing, the statue’s features are obscured. While the goal of this statue would have previously been recognition of the image and status of Queen Victoria, it now resists readability. It can no longer function as a status symbol without first wading through the history of colonization that the batik pattern represents.

Other pieces of Shonibare’s work continue to play with recognizable figures. One of my personal favorites is his recreation of Fragonard’s The Swing. It’s incredible how well he’s able to capture midair movement in a still, three-dimensional sculpture. The viewer becomes a part of the iconic painting and allowed a shifting view of a scene that, for so long, has only been viewed from one angle. Much like Gay Victorians, the headless mannequin shifts the focus to the posing and costuming, rather than allowing the viewer to only pay attention to the face. The installation of the piece in the room itself makes it seem like it is growing out into the space. The pose of the figure in the original painting has been captured so precisely yet completely re-contextualized and transformed by Shonibare.

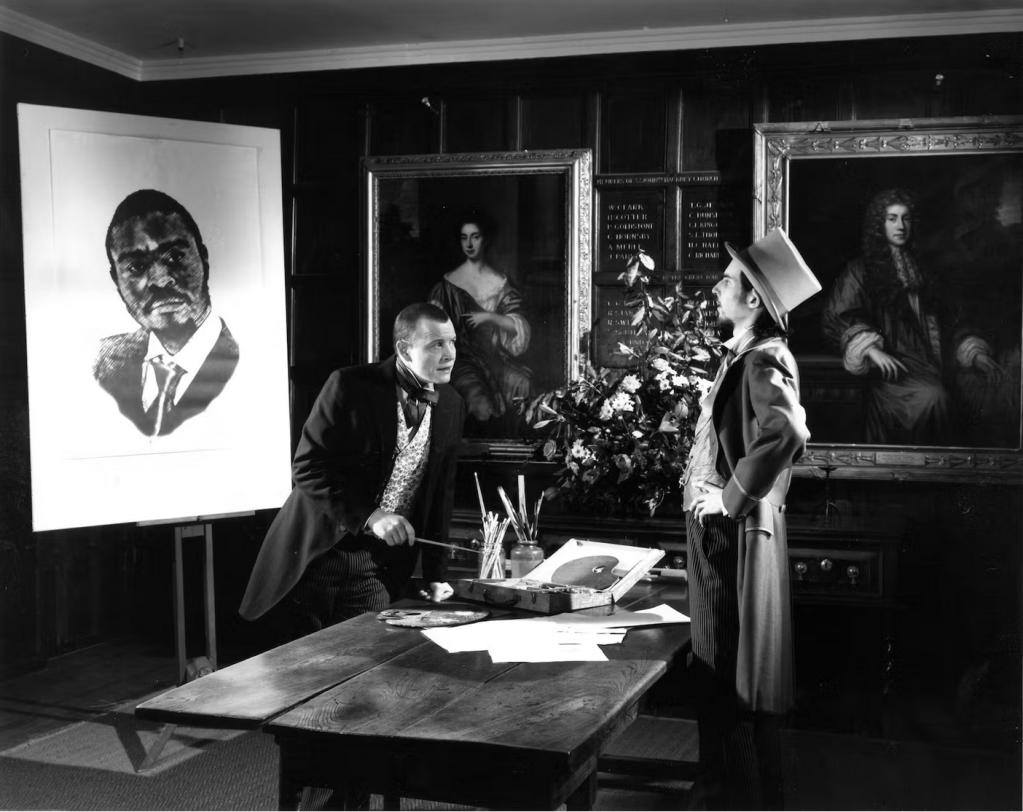

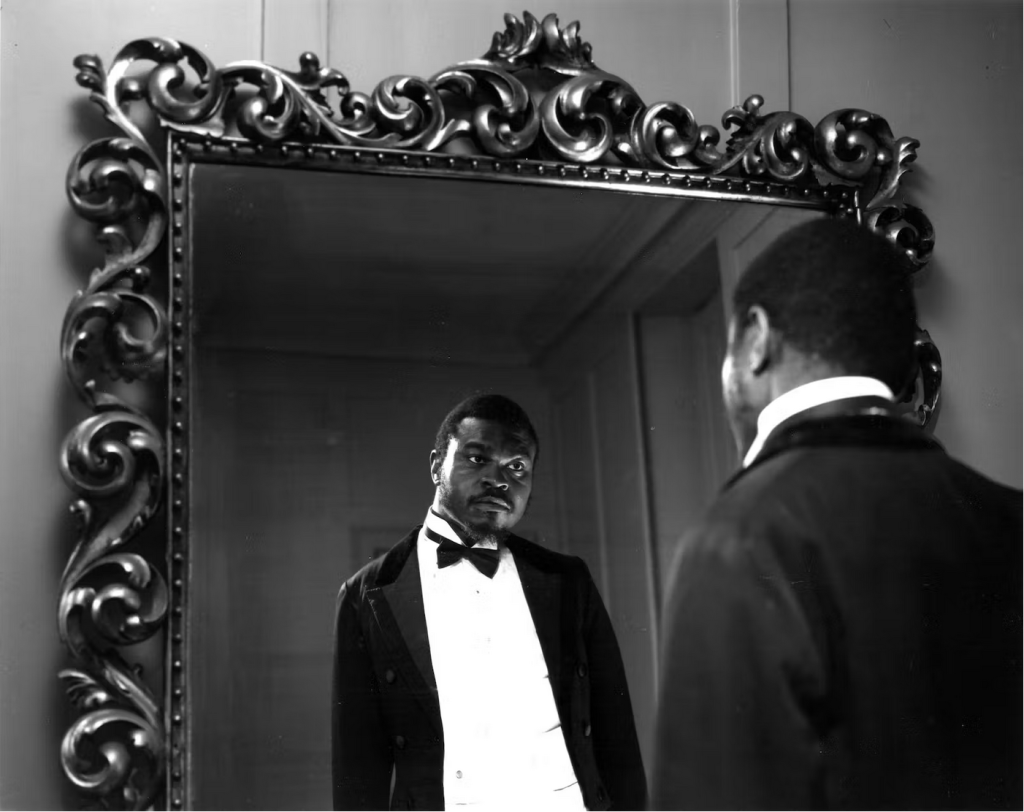

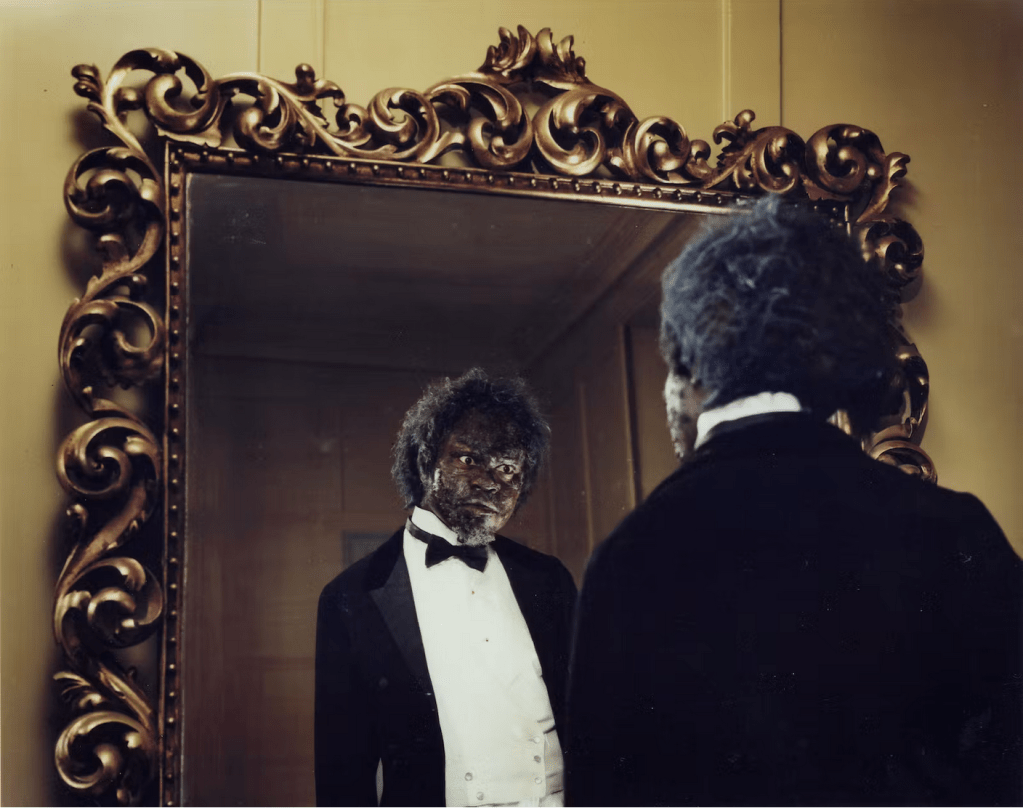

I’ve included one more of his works below, since it’s especially relevant to this course’s material. Dorian Gray is a collection of 12 photographic prints in the style of film stills made in 2001. Key scenes from the original novel are recreated in black and white. When collected together, the use of color when Dorian looks at his changed face in the mirror is striking.

Shonibare’s work ranges across many mediums, each requiring their own complete skill set. His work with textiles, sculpture, paint, and photography are all excellently done. I haven’t even touched on his large scale metalwork installations or filmography. It’s very impressive that he’s able to produce varied and well-made art within so many mediums, while each individual piece is still stylistically recognizable as his.

Thank you so much for introducing me to Shonibare’s brilliant work! Your readings of “Gay Victorians” and “Decolonized Structures” are sophisticated and insightful, and really open up the anticolonial critique of these pieces. I want to take some time with the Dorian Gray photographs in particular because I’m now fascinated with the ways that Shonibare uses a retelling of the novel to explore self-portraiture, race, and mirrors. Maybe I will include this series the next time I teach this course!

By: amartinmhc on December 24, 2023

at 9:57 am