After looking at many photographs by Lady Clementina Hawarden I realized how deliberate every choice in each composition was, and I’m deeply impressed by how she utilized posture, props, and lighting to create drastically different effects in her photographs. A unifying factor in her work is the relatively simple space and background, which focuses attention on the figures and any props included. A common setting for her figures was in front of a large window, and in many of her works she used natural light from a window rather than studio lighting. This was not common practice for photographers of the time and was highly experimental. As mentioned in class, Hawarden was working at the cusp of photography being considered ‘art’ and in her photographs we can see her experimenting with light, reflections, costumes and poses. Lady Hawarden did not title her photographs, calling them only “Studies from Life” or “Photographic Studies”, and many of her works appear to be studies of light and shadow and the way they interact with fabric and the female form. She also often used mirrors to reflect images of her subjects (often her daughters Clementina Maude and Isabella Grace), and we discussed in class how these transgressive mirror-versions are visible, yet inaccessible.

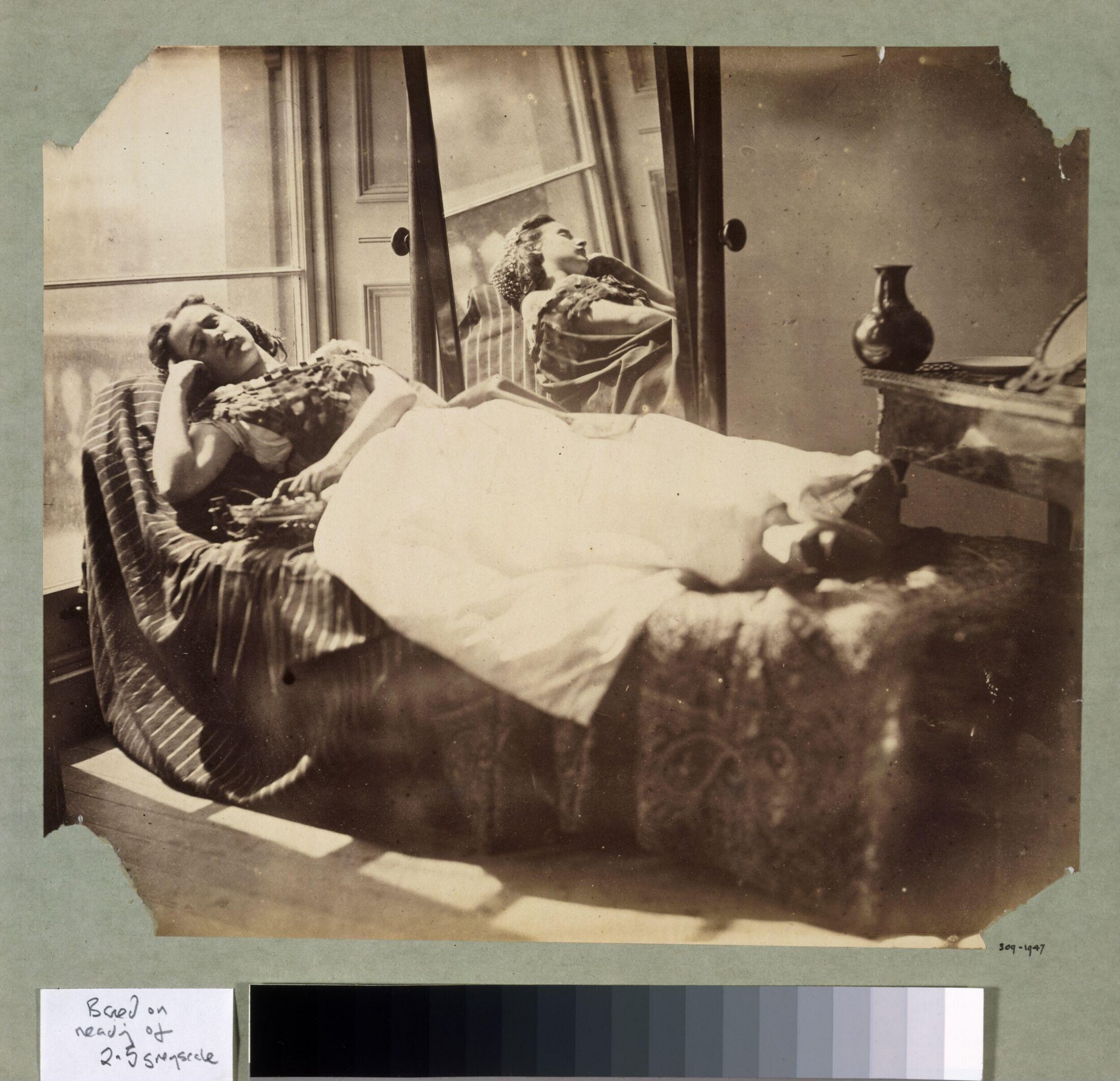

These are my favorite of her photographs, which at first may appear to be the same. The color of the photographs is different, which may be a product of their development or aging, but there are other intentional differences between the two. In the first photograph, the light casts the half of Clementina Maude’s face nearest the viewer into shadow while illuminating the half of her face that is reflected in the mirror. The light is reflected from her dress so brightly that it has a flattening effect on her body, creating a sense of unreality amplified by the shadow of her real-self and the illuminated view of her mirror-self. Squares of light from the window are cast around her body on the floor, creating a sense of illumination from below as well. She is posed with her head resting on her hand, recalling a classical Greek posture of contemplation, and the vase placed on a nearby table evokes classical ideals about female proportions. There is another blank mirror visible on the table, and Clementina Maude’s hand rests on a fruit basket, a symbol of sensuality, tucked close to her body.

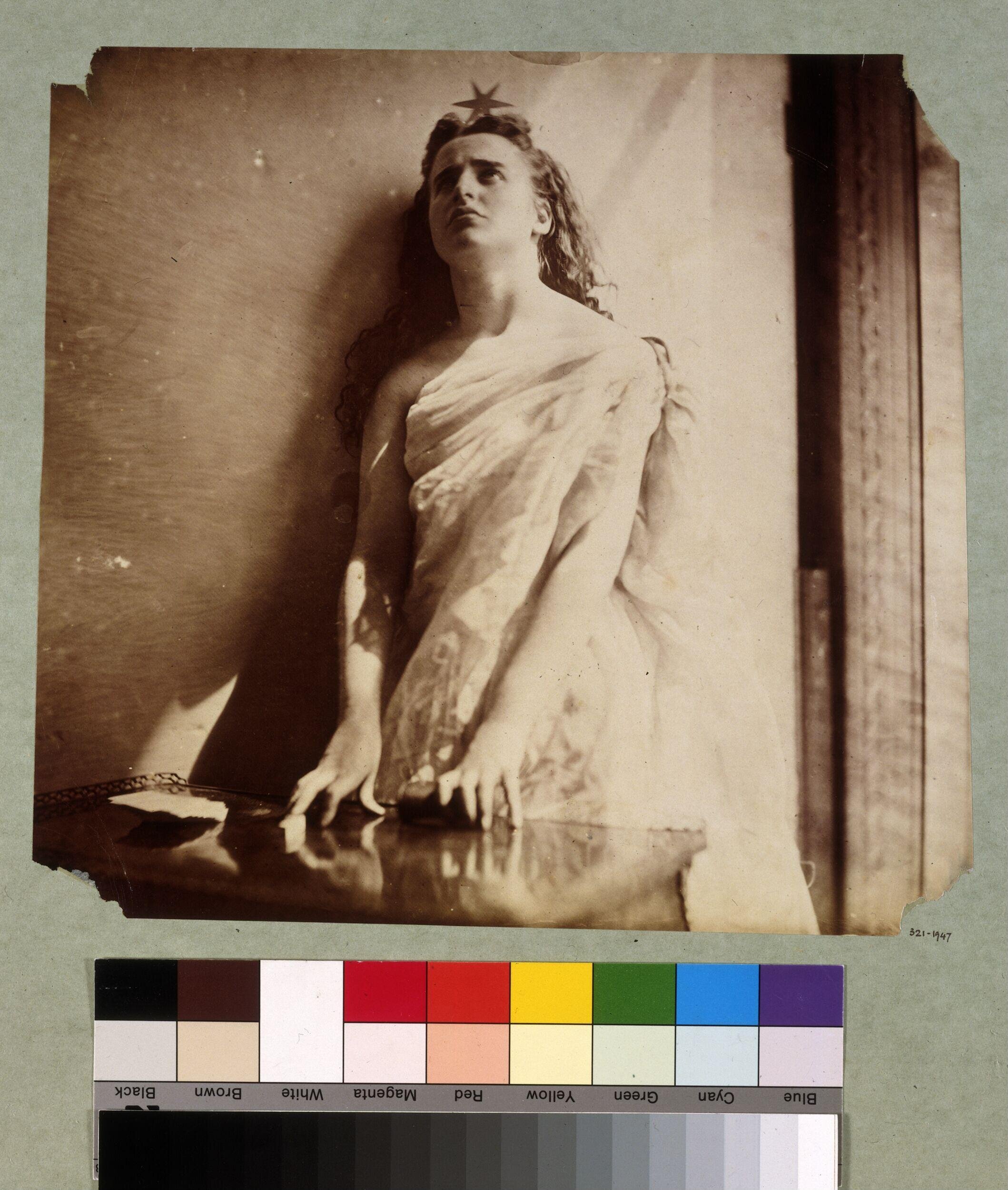

The second photograph appears much the same at first glance, but careful inspection reveals that the small mirror on the table is not visible and the fruit basket has been removed. The most striking difference to me is the effect created by the changed angle of the light. In the second photograph, the natural light from the window also illuminates her dress, but in such a way that the folds and physicality of the fabric are visible. The light also highlights her full face, both facing the viewer and reflected in the mirror, and paints sharp diagonals on the wall that balance the sharp angles of Clementina Maude’s arm. The second photograph feels much more grounded in reality and creates a sense of serenity and contemplation while the first photograph feels almost immaterial and transcendental (to me, at least).

I find it amazing that Lady Hawarden was able to create such different atmospheres by merely changing the angle of the light and moving a few props, and it shows how intentional every choice in posture, prop, and lighting was for her work. I’ve included some more of my favorites that I feel show this intentionality:

I also wanted to include some more of the ‘narrative-like’ photographs I found while looking through Lady Hawarden’s work that suggest a scene. I found it particularly intriguing that there is a whole series of photographs where Clementina Maude, dressed in men’s clothing, interacts with Isabella Grace, who wears fancy dress or clothing like that of Mary, Queen of Scots. These photographs create elaborate narrative scenes that feel quite different from the scenes where both of them are in women’s clothing. These scenes evoke the idea of courtship, and I find it interesting that Lady Hawarden created these scenes with her daughters who were around the age of becoming eligible for marriage.

Sources:

Harris, Leila Anne. “Lady Clementina Hawarden, Clementina and Florence Elizabeth Maude.” Smarthistory, smarthistory.org/lady-clementina-hawarden-clementina-and-florence-elizabeth-maude/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2025.

“Lady Clementina Hawarden – an Introduction · V&A.” Victoria and Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/lady-clementina-hawarden-an-introduction#:~:text=Lady%20Clementina%20Hawarden%20(1822%20%E2%80%93%2065,her%20life%20remains%20a%20mystery. Accessed 9 Dec. 2025.

Walker, Dave. “The First Fashion Photographer: Clementina, Lady Hawarden.” The Library Time Machine, 23 Sept. 2014, rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2012/10/04/the-first-fashion-photographer-clementina-lady-hawarden/.

Images from the Victoria and Albert Museum and Walker.

I really like your analysis of her work and the photos you’ve pulled out, they are beautiful! One of my favorite things about these photos is the tears on the corners, it just adds something so personal and makes it feel like you can see the history that’s accumulated since they were first displayed.

By: Sophie Frank on December 9, 2025

at 1:21 pm

Fascinating analysis! I find the last image of her two daughters dressed up in their costumes absolutely jaw dropping. The shadows working with the hat, and the way both the detail of the door and dress are in focus, while the left side of the image fades into obscurity. Truly such a piece of art.

By: juliamorrison on December 16, 2025

at 6:27 pm